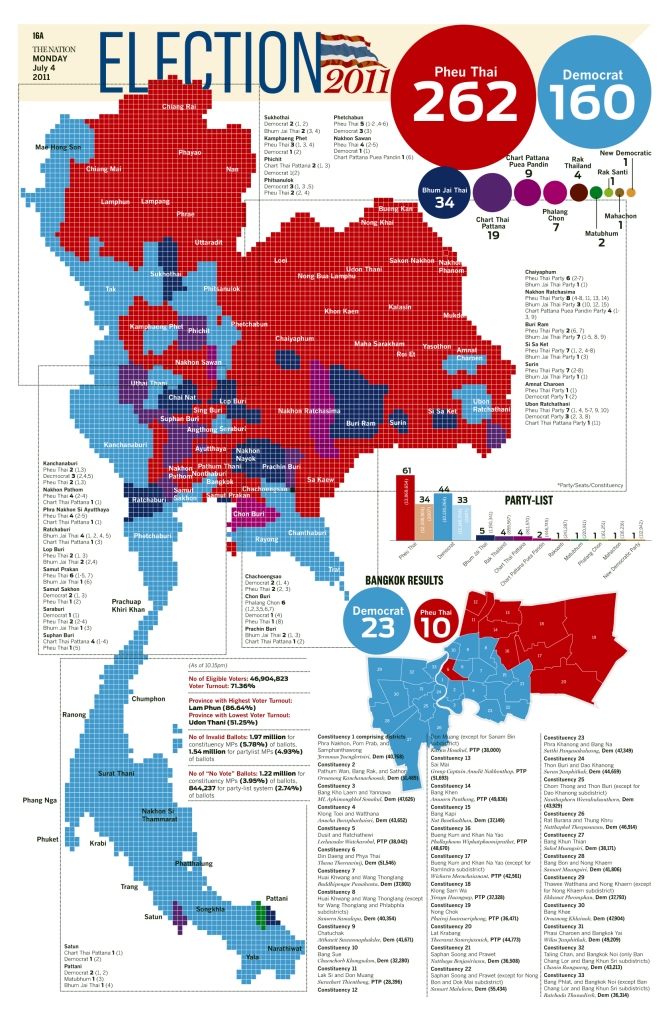

On May 30, the chieftain of the recently formed Thai military junta, General Prayuth Chan-ocha delievered a televised speech stating that elections would not be held until a year and three months later, a development that constituted another heavy blow to the pro-Thaksin Pheu Thai Party and its associated mass organization, the United Front for Democracy Against Dictatorship (UDD, commonly known as Red Shirts). Representing an old guard institution with enormous amount of rancor towards Pheu Thai’s populist politics, General Prayuth’s speech had made it very clear that the military is plotting to use all means possible to prevent a Pheu Thai return to power. In the next 454 days, the party must prepare for a fierce struggle to recapture its former powers lost to the military on the coup d’état of May 22. Supported by the populous north and northeastern provinces, Pheu Thai would likely score a decisive victory in the upcoming the general election, given it would be free and fair. Nevertheless, Pheu Thai must quickly mold into shape a comprehensive strategy to consolidate and expand its clout over the Thai voters. The following ten recommendations represent my personal view of how Pheu Thai should ready itself, as well as its allies to overcome the obstacles ahead and secure a landslide electoral victory in 2015.

Recommendations on political positioning:

- Do not attempt to play the role of the Great Conciliator. Focus the limited resources on party construction and electoral objectives. History has repeatedly shown the enduring difficulties in closing the social barriers created by economic disparity in a deeply polarized nation. For the latest example of a failed “bipartisan peacemaker”, Google “Barack Obama”.

- Transform policies and principles associated with Thaksin into a coherent ideology. The enterprising statesman’s unique approach in confronting challenges endemic to Thaialnd is without a doubt widely respected by voters across all strata of Thai society. In other words, the time is ripe to formulate an -ism that would cement Thaksin’s towering place in Thai politics for generations to come. Moreover, a 10-points or 5-points party program for the future of Thailand based upon Thaksinism would be more than helpful in channeling the party’s vision to Thai voters and the global audience.

Recommendations on party construction:

- Expand the Red Shirt Village movement to areas beyond the Thai countryside. While securing the loyalty of rural Thailand is fundamental to Pheu Thai’s existence, the party must simultaneously ensure firm urban support for its ideals. The Red Shirt Village movement should be further augmented into major Thai cities, one urban unit at a time. However, do make sure to tone down on the ostentatious ceremonial aspects because urban centers are very diverse in terms of political surroundings. Initially, the cities of the north and northeast would be great experimental plots for such strategy.

- Establish auxiliary organizations, mainly youth organizations. Getting the youth involved in the country’s politics is pivotal. Like in Western countries, political discussion clubs may be formed to educate the future leaders of the nation on their share of the task.

- Restrain firebrands in both Pheu Thai and UDD. If the upcoming election is free and fair, a Pheu Thai electoral victory is ineluctable. For this reason, any recklessness from the Young Turks of the party and UDD would jeopardize the party’s chances and play directly into the hands of the junta. The ensanguined crackdown on Red Shirt demonstrators during April 2010 had made clear that the Thai military has no qualms in mowing down peaceful protesters. So instead of throwing human flesh against fusillades of live rounds, taking power via the ballot box is the most cost-effective method.

- Prepare immediately for the formation of a new party. The military junta, led by the hostile General Prayuth Chan-ocha is likely going to attempt to dislodge and destroy the Pheu Thai Party by any means necessary. A cause célèbre harkening back to the 2007 court dissolution of the pro-Thaksin Thai Rak Thai Party is much closer to reality than one could imagine. Therefore, while seeking to consolidate and expand the party’s power, Pheu Thai must bite-the-bullet prepare for this imminent danger by grooming next-generation party leaders and organize all other necessities needed for a new party.

Recommendations on forging alliance:

- Construct a united front with responsive elements of society. Every time the Thai military conducts a coup d’état it looses the support of some sections of society. Pheu Thai and associated organizations need to make overtures to these disgruntled groups, and win them over in the next election. Though anti-coup individuals might not be amenable to all of Pheu Thai’s ideals, their resolute stance in preserving and safeguarding the democratic process more than complement Pheu Thai’s political aspirations.

- Win over central, southern, and eastern voters. This could be quite difficult due to the stratification of Thai society along socio-economic and regional lines. But the inclusion of more politicians with central, southern, and eastern background could be a starting point. Besides enhancing the party’s mass appeal, they may serve as barometers of their home region’s popular sentiments vis-à-vis Pheu Thai. Either way, an initiative should be made to puncture the regional divide for the future success of Pheu Thai as a genuinely national party.

Recommendations on conducting international work:

- Initiate massive global public relations campaigns to garner international support for Pheu Thai’s cause. Mobilizing international public opinion would be an influential factor in shaping domestic preferences in the upcoming election. In addition to publicity drives through multimedia mediums, significant figures of Pheu Thai, or perhaps UDD should travel abroad on speaking tours with the mission of emphasizing the importance of the world’s support to Pheu Thai’s struggle for the indigent population of Thailand.

- Invite international observers to ensure the next general election is free and fair. Already planning to rewrite the constitution, the military and its political cronies are most likely going to tweak the election by quasi-legal or worse, illegal means to make the results favorable for Pheu Thai’s nemesis, the Democrat Party. Thus, the invitation of international observers may function as a stricture on the military’s furtive designs to impede Pheu Thai’s march towards a total electoral victory.

(Copyright 2014 Zi Yang)